(1) On termination of a contract to be performed at one time either party may claim restitution of whatever it has supplied under the contract, provided that such party concurrently makes restitution of whatever it has received under the contract.

(2) If restitution in kind is not possible or appropriate, an allowance has to be made in money whenever reasonable.

(3) The recipient of the performance does not have to make an allowance in money if the impossibility to make restitution in kind is attributable to the other party.

(4) Compensation may be claimed for expenses reasonably required to preserve or maintain the performance received.

COMMENT

1. Contracts to be performed at one time

This Article refers only to contracts to be performed at one time. A different regime applies to contracts under which the characteristic performance is to be made over a period of time (see Article 7.3.7). The most common example of a contract to be performed at one time is an ordinary contract of sale where the entire object of the sale has to be transferred at one particular moment. This Article however refers also to, e.g. construction contracts in which the contractor is under an obligation to produce the entire work to be accepted by the customer at one particular time. A turnkey contract provides an important example.

Under a commercial contract one party will usually have to pay money for the performance received. That obligation is not the one that is characteristic of the contract. Thus, a contract of sale where the purchase price has to be paid in instalments, will fall under this Article provided that the seller’s performance is to be made at one time.

2. Right of parties to restitution on termination

Paragraph (1) of this Article gives each party a right to claim the return of whatever the party has supplied under the contract provided that that party concurrently makes restitution of whatever it has received.

Illustration

1. In the process of a takeover of a company, controlling shareholder A agrees to sell and transfer to B shares for GBP 1,000,000. B only pays GBP 600,000 after the shares have been transferred and A therefore terminates the contract. A can claim back the shares. At the same time, A has to return the GBP 600,000 received from B.

This rule also applies when the aggrieved party has made a bad bargain. If, in the case mentioned in Illustration 1, the real market value of the shares is GBP 1,200,000, A may still require the return of the shares.

This Article also applies to the situation where the aggrieved party has supplied money in exchange for property, services, or other performances which the party has not received or which are defective.

Illustration

2. Art dealer A sells a Constable painting to art dealer B for EUR 600,000. B only pays EUR 200,000 for the painting, and A therefore terminates the contract. Subsequently it turns out that the painting is not a Constable but a copy. On termination of the contract, B can reclaim the purchase price and must return the painting to A.

As regards the costs involved in making restitution, Article 6.1.11 applies.

3. Restitution in kind not possible or appropriate

Restitution must normally be made in kind. There are, however, instances where instead of restitution in kind, an allowance in money has to be made. This is the case first of all where restitution in kind is not possible. The allowance will normally amount to the value of the performance received.

Illustrations

3. Company A, which has contracted to excavate company B’s site, leaves it after only part of the work has been done. B, which then terminates the contract, will have to pay A a sum in compensation for the work done, measured by the value that work has for B. At the same time B will have a claim against A for whatever damages B may have suffered as a result of A’s breach of contract (see Article 7.3.5 (2)).

4. Company A charters a ship for a company cruise for its employees which is to take them up the Australian Coral Reef. Half-way the cruise ship breaks down and cannot continue the cruise. A terminates the contract with B, the owner of the business organising the cruise, and decides to fly its employees home. If A had already paid the price A can now claim it back. At the same time, A owes B an allowance amounting to the value of the cruise so far. In addition, A can claim damages for the loss suffered as a result of B’s non-performance (see Article 7.3.5 (2)).

An allowance is further envisaged by paragraph (2) of this Article whenever restitution in kind would not be appropriate. This is so in particular when returning the performance in kind would cause unreasonable effort or expense. The standard, in that respect, is the same as under Article 7.2.2(b).

Illustration

5. A, an artist, sells 200 silver-plated rings to dealer B. B fails to pay for the rings and A thereupon terminates the contract. It turns out that B has, in the meantime, attempted to ship the rings to his business premises. However, the boat on which they had been stored has sunk. Although it would be possible, at great expense, to rescue the rings from the wrecked ship, this cannot be expected of B. B has to pay a reasonable sum to A, measured by the value of the rings.

The purpose of specifying that an allowance has to be made in money “whenever reasonable” is to make it clear that an allowance only has to be made if, and to the extent that, the performance has conferred a benefit on its recipient. That is not the case, for example, where the defect which gives the recipient of the performance a right to terminate has only become apparent in the course of processing the object of that performance.

Illustration

6. Company A hires company B to develop a specialised software to improve its existing internal communication system. Once B has developed and installed the software, the software does not perform the functions it was intended to. A can terminate the contract and re-claim the price paid, but since the installed system has no value for A, it would not be reasonable to expect A to pay B an allowance for the installed software.

4. The allocation of risk

The rule contained in paragraph (2) implies an allocation of risk: it imposes a liability on the recipient of the performance to make good the value of that performance if it is unable to make restitution in kind. The rule in paragraph (2) applies even if the recipient was responsible for the deterioration or destruction of what it had received. Such allocation of the risk of deterioration or destruction is justified, in particular, because the risk should lie with the person in control of the performance. On the contrary, there is no liability to make good the value where the deterioration or destruction is attributable to the other party: either because it was due to the other party’s fault, or because it was due to a defect inherent in the performance. Hence the rule in paragraph (3).

Illustration

7. Manufacturer A sells and delivers a luxury car to company B. The car has defective brakes. Due to this defect it crashes into another car and is totally destroyed. Since the car was unfit to be used for its intended purpose, B can terminate the contract and reclaim the purchase price. B does not have to make an allowance for not being able to return the car.

The recipient’s liability to make good the value of the performance received is not excluded in cases where the deterioration or destruction would also have occurred had the performance not been rendered.

Illustration

8. Manufacturer A sells and delivers a car to company B. After delivery has taken place, the car is totally destroyed by a hurricane flooding the properties of both A and B. B terminates the contract because of a defect attaching to the car. B can reclaim the purchase price but, at the same time, has to make an allowance for the value of the car prior to its destruction.

The question of the recipient’s liability to pay the value of the performance only arises in cases where the deterioration or destruction occurs before termination of the contract. If what has been performed deteriorates or is destroyed after termination of the contract, the normal rules on non-performance apply, as after termination the recipient of the performance is under a duty to return what the recipient has received. Any non-performance of that duty gives the other party a right to claim damages according to Article 7.4.1, unless the non-performance is excused under Article 7.1.7.

Illustration

9. Company A sells and delivers to company B a limousine with a leaking roof. Since the limousine is unfit to be used for its intended purpose, B can terminate the contract. As a result, B can reclaim the purchase price but is under a duty to return the limousine. Before B can return the car it is totally destroyed by a thunderstorm. A cannot claim damages because B is excused under Article 7.1.7.

5. Compensation for expenses

The recipient of a performance may have incurred expenses for the preservation or maintenance of the object of the performance. It is reasonable to allow the recipient to claim compensation for these expenses where the contract has been terminated and where, therefore, the parties have to return what they have received.

Illustration

10. Company A has sold and delivered a race horse to company B. Some time later it becomes apparent that the horse is not, as A had promised, a descendant of a particular stallion. B terminates the contract. B can claim compensation for the costs incurred in feeding and caring for the horse.

This rule applies only to reasonable expenses. What is reasonable depends on the circumstances of the case. In Illustration 10 it would matter whether the horse had been sold as a race horse or as an ordinary farm horse.

Compensation cannot be claimed for other expenses linked to the performance received, even if they are reasonable.

Illustration

11. Company A has sold and delivered a software package to company B. B then discovers that the software is lacking a certain functionality it was supposed to have. B therefore asks software expert C to check whether that functionality can still be implemented. Since that turns out not to be possible, B terminates the contract. B cannot recover the fee paid to C as expenses under paragraph (4) from A.

6. Benefits

The Principles do not take a position concerning benefits that have been derived from the performance, or interest that has been earned. In commercial practice it will often be difficult to establish the value of the benefits received by the parties as a result of the performance. Furthermore, often both parties will have received such benefits.

7. Rights of third persons not affected

In common with other Articles of the Principles, this Article deals with the relationship between the parties and not with any rights on the goods concerned that third persons may have acquired. Whether, for instance, an obligee of the buyer, the buyer’s receivers in bankruptcy, or a purchaser in good faith may oppose the restitution of goods sold is to be determined by the applicable law.

Prof. Leonardo Fabio Pastorino is Full Professor of Agricultural and Food Law at the University of Verona (since 2021), where he teaches Agri-Food Law; Agri-Environmental Innovation and Sustainability Law; Agricultural Law for Development and Innovation; and Comparative Agri-Food Law. He previously served as Full Professor of Agricultural Law at the Universidad Nacional de La Plata (Faculty of Legal and Social Sciences, full-time), where he began his academic career in 1993 and progressed through academic ranks from assistant to associate professor to full professor. He was also Full Professor of Renewable Natural Resources Law at the Universidad Nacional de La Plata (Faculty of Natural and Museum Sciences).

Prof. Leonardo Fabio Pastorino is Full Professor of Agricultural and Food Law at the University of Verona (since 2021), where he teaches Agri-Food Law; Agri-Environmental Innovation and Sustainability Law; Agricultural Law for Development and Innovation; and Comparative Agri-Food Law. He previously served as Full Professor of Agricultural Law at the Universidad Nacional de La Plata (Faculty of Legal and Social Sciences, full-time), where he began his academic career in 1993 and progressed through academic ranks from assistant to associate professor to full professor. He was also Full Professor of Renewable Natural Resources Law at the Universidad Nacional de La Plata (Faculty of Natural and Museum Sciences).

José Angelo Estrella Faria is a Brazilian lawyer and former career staff member of the United Nations, lately (until November 2024) as Principal Legal Officer with the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL), where he supervised the work of UNCITRAL on digital economy, insolvency law and negotiable cargo documents. He also acted as secretary of the working group that prepared the UN Convention on the International Effects of Judicial Sales of Ships.

José Angelo Estrella Faria is a Brazilian lawyer and former career staff member of the United Nations, lately (until November 2024) as Principal Legal Officer with the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL), where he supervised the work of UNCITRAL on digital economy, insolvency law and negotiable cargo documents. He also acted as secretary of the working group that prepared the UN Convention on the International Effects of Judicial Sales of Ships. Herbert Kronke, a national of Germany, served as Secretary-General of UNIDROIT from 1998-2008.

Herbert Kronke, a national of Germany, served as Secretary-General of UNIDROIT from 1998-2008. Professor Marc-André Renold, Dr. iur., LL.M. (Yale), studied law and the humanities at the Universities of Geneva and Basel in Switzerland and at Yale University in the USA. Professor Renold is the co-holder of the UNESCO Chair on the international law of the protection of cultural heritage at the University of Geneva, which he established in 2012. He also founded its Art-Law Centre of which he was a Director until August 2023, when he was appointed honorary Professor of the University of Geneva.

Professor Marc-André Renold, Dr. iur., LL.M. (Yale), studied law and the humanities at the Universities of Geneva and Basel in Switzerland and at Yale University in the USA. Professor Renold is the co-holder of the UNESCO Chair on the international law of the protection of cultural heritage at the University of Geneva, which he established in 2012. He also founded its Art-Law Centre of which he was a Director until August 2023, when he was appointed honorary Professor of the University of Geneva. Vincent Negriis a lawyer and senior researcher at the Institute for Social Sciences of Politic (Institut des Sciences sociales du Politique – UMR 7220), ENS Paris-Saclay.

Vincent Negriis a lawyer and senior researcher at the Institute for Social Sciences of Politic (Institut des Sciences sociales du Politique – UMR 7220), ENS Paris-Saclay. A graduate of the French ENA (Ecole Nationale d’Administration) and of the

A graduate of the French ENA (Ecole Nationale d’Administration) and of the Ana Filipa Vrdoljak is Professor of Law and the UNESCO Chair in International Law and Cultural Heritage. She is co-coordinator of the UNESCO-UNITWIN Network on Culture in Emergencies. She is the author of International Law, Museums and the Return of Cultural Objects (Cambridge University Press, 2006 and 2008, forthcoming 2e 2025) and editor of Oxford Handbook on International Cultural Heritage Law with Francesco Francioni (Oxford University Press 2020), The Cultural Dimension of Human Rights (Oxford University Press, 2013) and International Law for Common Goods: Normative Perspectives in Human Rights, Culture and Nature with Federico Lenzerini (Hart Publishing, 2014), and Oxford Commentary on the 1970 UNESCO and 1995 UNIDROIT Conventions with Andrzej Jakubowski and Alessandro Chechi (Oxford University Press, 2024).

Ana Filipa Vrdoljak is Professor of Law and the UNESCO Chair in International Law and Cultural Heritage. She is co-coordinator of the UNESCO-UNITWIN Network on Culture in Emergencies. She is the author of International Law, Museums and the Return of Cultural Objects (Cambridge University Press, 2006 and 2008, forthcoming 2e 2025) and editor of Oxford Handbook on International Cultural Heritage Law with Francesco Francioni (Oxford University Press 2020), The Cultural Dimension of Human Rights (Oxford University Press, 2013) and International Law for Common Goods: Normative Perspectives in Human Rights, Culture and Nature with Federico Lenzerini (Hart Publishing, 2014), and Oxford Commentary on the 1970 UNESCO and 1995 UNIDROIT Conventions with Andrzej Jakubowski and Alessandro Chechi (Oxford University Press, 2024). Vesselina Haralampieva is Head of Sustainable Finance Governance and Regulation and Senior Counsel at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in London. In this role, she leads a team driving strategic climate change and sustainability policy initiatives and drives legal reforms in sustainable finance, ESG reporting, and energy transition.

Vesselina Haralampieva is Head of Sustainable Finance Governance and Regulation and Senior Counsel at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in London. In this role, she leads a team driving strategic climate change and sustainability policy initiatives and drives legal reforms in sustainable finance, ESG reporting, and energy transition. Elif Dilek Yilmaz is an Associate Counsel in the Sustainable Finance Governance & Regulation Unit of the Legal Transition Team at European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). Her work focuses on strengthening legal, regulatory, and governance frameworks that enable private-sector transition toward sustainability, with a particular emphasis on climate corporate governance, transition planning, sustainable finance taxonomies, and sector-level reforms. She contributes to both policy dialogue and investment-related activities in EBRD economies and is also involved in the development of analytical tools and guidance materials for boards, regulators and policymakers.

Elif Dilek Yilmaz is an Associate Counsel in the Sustainable Finance Governance & Regulation Unit of the Legal Transition Team at European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). Her work focuses on strengthening legal, regulatory, and governance frameworks that enable private-sector transition toward sustainability, with a particular emphasis on climate corporate governance, transition planning, sustainable finance taxonomies, and sector-level reforms. She contributes to both policy dialogue and investment-related activities in EBRD economies and is also involved in the development of analytical tools and guidance materials for boards, regulators and policymakers. Belinda is a senior legal professional with more than 25 years’ experience in law, regulation, policy and negotiation relating to Banking, Trading and Finance across Global Markets, Energy and Sustainable Finance. Previous roles include MD, global head for commodities legal and sustainable financing at Citibank, global head of commodities legal Deutsche Bank AG and private practice Energy and Infrastructure at Hogan Lovells. Belinda now focuses on driving finance towards the goals of the Paris Agreement and mediated negotiation and dispute resolution. She acts as ● legal consultant ● senior advisor to IETA and ● mediator at Mediation1st UK.

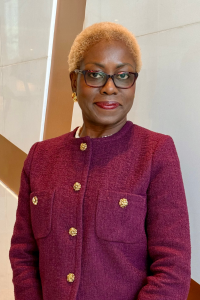

Belinda is a senior legal professional with more than 25 years’ experience in law, regulation, policy and negotiation relating to Banking, Trading and Finance across Global Markets, Energy and Sustainable Finance. Previous roles include MD, global head for commodities legal and sustainable financing at Citibank, global head of commodities legal Deutsche Bank AG and private practice Energy and Infrastructure at Hogan Lovells. Belinda now focuses on driving finance towards the goals of the Paris Agreement and mediated negotiation and dispute resolution. She acts as ● legal consultant ● senior advisor to IETA and ● mediator at Mediation1st UK. Emilia Onyema is an independent arbitrator and a Professor of International Commercial Law at SOAS University of London where she teaches international commercial arbitration, international investment law and commercial law in a global context. She is qualified to practice law in Nigeria, as a Solicitor in England & Wales, and Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators. She convenes the SOAS Arbitration in Africa conference series and leads the SOAS Arbitration in Africa biennial survey research project; she co-authored the African Promise and is the Director of the SOAS Arbitration and Dispute Resolution Centre. Her research interests focus on the development of international arbitration in Africa and the engagement of Africans in international arbitration. She has experience as presiding, co and sole arbitrator, and acts as legal expert witness in international arbitration. She actively publishes and speaks on topics relevant to her research interests. Some of her publications include, International Commercial Arbitration and the Arbitrator’s Contract (Routledge, 2010); Rethinking the Role of African National Courts in Arbitration (Kluwer, 2018), “Reimagining the Framework for resolving Intra-African Commercial Disputes in the Context of the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement”, World Trade Review (2019); and “African Practitioners, International Arbitration, and Inclusivity” (ICCA Congress Series No 21, 2022). In 2024, she received the CPR Institute award for “Outstanding Contribution to Diversity in ADR”, and the African Arbitration Association award for Publication/Speech of the Year for

Emilia Onyema is an independent arbitrator and a Professor of International Commercial Law at SOAS University of London where she teaches international commercial arbitration, international investment law and commercial law in a global context. She is qualified to practice law in Nigeria, as a Solicitor in England & Wales, and Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Arbitrators. She convenes the SOAS Arbitration in Africa conference series and leads the SOAS Arbitration in Africa biennial survey research project; she co-authored the African Promise and is the Director of the SOAS Arbitration and Dispute Resolution Centre. Her research interests focus on the development of international arbitration in Africa and the engagement of Africans in international arbitration. She has experience as presiding, co and sole arbitrator, and acts as legal expert witness in international arbitration. She actively publishes and speaks on topics relevant to her research interests. Some of her publications include, International Commercial Arbitration and the Arbitrator’s Contract (Routledge, 2010); Rethinking the Role of African National Courts in Arbitration (Kluwer, 2018), “Reimagining the Framework for resolving Intra-African Commercial Disputes in the Context of the African Continental Free Trade Area Agreement”, World Trade Review (2019); and “African Practitioners, International Arbitration, and Inclusivity” (ICCA Congress Series No 21, 2022). In 2024, she received the CPR Institute award for “Outstanding Contribution to Diversity in ADR”, and the African Arbitration Association award for Publication/Speech of the Year for  María Ignacia Vial Undurraga is Professor of Private International Law at Universidad de los Andes and at the Pontificia Universidad Católica, both of Santiago, Chile. She holds a DPhil (Doctor of Philosophy) degree from King´s College, London. She is a qualified lawyer before the Chilean Supreme Court and a Bachelor of Laws from the Pontificia Universidad Católica, Santiago, Chile. She is also a founder member of ADIPRI, the Chilean Association of Private International Law and co-drafter of the 2020, Bill of the Chilean Act on Private International Law. Likewise, she is an associated member of IHLADI, the Hispano-Portuguese American Institute of International Law. She has been a visiting researcher at the UNIDROIT Institute (Rome) and at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law (Hamburg). She is a member of UNIDROIT´s Governing Council for the 2024-2028 period and Chair of its Working Group on Collaborative Legal Structures for Agricultural Enterprises. Her area of research is focused on Private International Law and, specifically, the law applicable to international contracts, to international precontractual liability, to international matrimonial regimes and to international corporations; besides, she has developed research on sustainability duties in contracts and corporations. She has published several papers in Chilean and foreign legal journals and delivered presentations in national and international academic conferences and seminars.

María Ignacia Vial Undurraga is Professor of Private International Law at Universidad de los Andes and at the Pontificia Universidad Católica, both of Santiago, Chile. She holds a DPhil (Doctor of Philosophy) degree from King´s College, London. She is a qualified lawyer before the Chilean Supreme Court and a Bachelor of Laws from the Pontificia Universidad Católica, Santiago, Chile. She is also a founder member of ADIPRI, the Chilean Association of Private International Law and co-drafter of the 2020, Bill of the Chilean Act on Private International Law. Likewise, she is an associated member of IHLADI, the Hispano-Portuguese American Institute of International Law. She has been a visiting researcher at the UNIDROIT Institute (Rome) and at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Private Law (Hamburg). She is a member of UNIDROIT´s Governing Council for the 2024-2028 period and Chair of its Working Group on Collaborative Legal Structures for Agricultural Enterprises. Her area of research is focused on Private International Law and, specifically, the law applicable to international contracts, to international precontractual liability, to international matrimonial regimes and to international corporations; besides, she has developed research on sustainability duties in contracts and corporations. She has published several papers in Chilean and foreign legal journals and delivered presentations in national and international academic conferences and seminars. Camila Villard Duran is an Associate Professor of Law at the ESSCA School of Management in France and a Brazilian lawyer. Her research examines international economic law, the regulation of money and financial systems, digital-asset governance, climate-finance frameworks, and gender equity in economic and legal institutions. She is one of the co-founders of the Institute of Women in Regulation in Brazil, a platform for collaboration and exchange of ideas and experiences among female professionals in regulatory fields.

Camila Villard Duran is an Associate Professor of Law at the ESSCA School of Management in France and a Brazilian lawyer. Her research examines international economic law, the regulation of money and financial systems, digital-asset governance, climate-finance frameworks, and gender equity in economic and legal institutions. She is one of the co-founders of the Institute of Women in Regulation in Brazil, a platform for collaboration and exchange of ideas and experiences among female professionals in regulatory fields. Jeannette M.E. Tramhel is an international lawyer who is currently Chair of the Sustainable Development Committee for the Centenary of UNIDROIT. She has worked with the legal secretariat of three international organizations, most recently as Senior Legal Consultant with UNIDROIT, prior thereto as Senior Legal Officer with the Organization of American States (OAS), and previously with the United Nations Commission for International Trade Law (UNCITRAL). As a result, she has developed an enriched understanding of the development of private international law, commercial and trade law, which she has applied in the management of technical assistance projects carried out in partnership with States embarking upon legislative implementation and domestic law reform to improve access to credit and simplify business incorporation. She holds an LL.M. from Georgetown University, an LL.B. from Queen’s University in Canada and is a member of the bar in New York and Ontario, Canada. Jeannette has also worked with the Government of Canada, practiced law with a major Canadian firm and taught various courses in international trade and business law.

Jeannette M.E. Tramhel is an international lawyer who is currently Chair of the Sustainable Development Committee for the Centenary of UNIDROIT. She has worked with the legal secretariat of three international organizations, most recently as Senior Legal Consultant with UNIDROIT, prior thereto as Senior Legal Officer with the Organization of American States (OAS), and previously with the United Nations Commission for International Trade Law (UNCITRAL). As a result, she has developed an enriched understanding of the development of private international law, commercial and trade law, which she has applied in the management of technical assistance projects carried out in partnership with States embarking upon legislative implementation and domestic law reform to improve access to credit and simplify business incorporation. She holds an LL.M. from Georgetown University, an LL.B. from Queen’s University in Canada and is a member of the bar in New York and Ontario, Canada. Jeannette has also worked with the Government of Canada, practiced law with a major Canadian firm and taught various courses in international trade and business law. Lisa DeMarco is a Senior Partner and CEO of Resilient. She is called to the bar in Canada and England and repeatedly recognized as a global expert in climate and energy law with three decades of experience in the sectors. She assists financial institutions, energy companies, innovators, governments, non-governmental organizations, and Indigenous business organizations on domestic and overseas renewable power and energy transition projects, sustainable and climate finance transactions, carbon dioxide removals and carbon capture use and storage, projects and transactions, climate and nature related financial disclosure, corporate climate risk, environmental and social governance (ESG), green bonds, claims, the Paris Agreement, carbon trading (domestic, international, voluntary, and compliance), climate-related compliance and litigation, and sustainable business

Lisa DeMarco is a Senior Partner and CEO of Resilient. She is called to the bar in Canada and England and repeatedly recognized as a global expert in climate and energy law with three decades of experience in the sectors. She assists financial institutions, energy companies, innovators, governments, non-governmental organizations, and Indigenous business organizations on domestic and overseas renewable power and energy transition projects, sustainable and climate finance transactions, carbon dioxide removals and carbon capture use and storage, projects and transactions, climate and nature related financial disclosure, corporate climate risk, environmental and social governance (ESG), green bonds, claims, the Paris Agreement, carbon trading (domestic, international, voluntary, and compliance), climate-related compliance and litigation, and sustainable business Ulrich G. Schroeter is a Professor of Law at the University of Basel (Switzerland). He has published extensively on matters of international trade law and commercial law (in particular the 1980 Vienna Sales Convention (CISG)), Swiss and German contract law, arbitration, treaty law and financial markets regulation. Professor Schroeter is the co-editor of the Commentary on the UN Convention on the International Sale of Goods (CISG) (Oxford University Press, 5th edition 2022, 2,160 pages) and the editor-in-chief of the CISG-online database (www.cisg-online.org). His current research inter alia focusses on the impact of supply chain regulations and of economic sanctions on cross-border trading relations, as well as on the challenges of international commercial law in times of climate change.

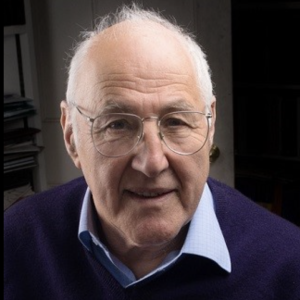

Ulrich G. Schroeter is a Professor of Law at the University of Basel (Switzerland). He has published extensively on matters of international trade law and commercial law (in particular the 1980 Vienna Sales Convention (CISG)), Swiss and German contract law, arbitration, treaty law and financial markets regulation. Professor Schroeter is the co-editor of the Commentary on the UN Convention on the International Sale of Goods (CISG) (Oxford University Press, 5th edition 2022, 2,160 pages) and the editor-in-chief of the CISG-online database (www.cisg-online.org). His current research inter alia focusses on the impact of supply chain regulations and of economic sanctions on cross-border trading relations, as well as on the challenges of international commercial law in times of climate change. Born in 1952 in Germany.High school in Germany and in the United States. Studies in law and French language in Saarbrücken and Geneva; qualification as a German judge in 1981. Post graduate studies in development issues and development law in Geneva and Paris. Licentiate, doctorate and professorship qualification incomparative law at the University of Helsinki.

Born in 1952 in Germany.High school in Germany and in the United States. Studies in law and French language in Saarbrücken and Geneva; qualification as a German judge in 1981. Post graduate studies in development issues and development law in Geneva and Paris. Licentiate, doctorate and professorship qualification incomparative law at the University of Helsinki. Lorenzo Cotula is the Head of the Law, Economies and Justice Programme at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), a policy research institute based in the United Kingdom. Lorenzo’s research and policy work cuts across international economic law, natural resource law, environmental law, human rights law and sustainable development. Alongside his role at IIED, Lorenzo was a Visiting Professor at Strathclyde Law School in 2017-2023 and, prior to that, he held visiting affiliations with Warwick and Dundee universities. Before joining IIED in 2002, Lorenzo worked as a research consultant to the Legal Office of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Lorenzo holds a degree in law (Sapienza University of Rome), an MSc in Development Studies (London School of Economics), a PhD in law (University of Edinburgh) and a PgCert in Sustainable Business (University of Cambridge).

Lorenzo Cotula is the Head of the Law, Economies and Justice Programme at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), a policy research institute based in the United Kingdom. Lorenzo’s research and policy work cuts across international economic law, natural resource law, environmental law, human rights law and sustainable development. Alongside his role at IIED, Lorenzo was a Visiting Professor at Strathclyde Law School in 2017-2023 and, prior to that, he held visiting affiliations with Warwick and Dundee universities. Before joining IIED in 2002, Lorenzo worked as a research consultant to the Legal Office of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Lorenzo holds a degree in law (Sapienza University of Rome), an MSc in Development Studies (London School of Economics), a PhD in law (University of Edinburgh) and a PgCert in Sustainable Business (University of Cambridge).  Dr. Marek Dubovec is the Director of Law Reform Programs at the International Law Institute (ILI). For over 15 years, Marek has been working with UNCITRAL and UNIDROIT to draft conventions, model laws, principles, and guides that assist States in modernizing their commercial law frameworks. He has worked on implementing these standards under projects funded by the World Bank Group, the EBRD, FSD-Kenya, and others. He has assisted countries in Africa (e.g., Kenya), Asia (e.g., the Philippines), Eastern Europe (e.g., Ukraine), the Middle East (e.g., the UAE), and Latin America (e.g., Colombia) with reforms of their frameworks on secured transactions, factoring, warehouse receipts, and related legislation. Marek has authored and co-authored numerous articles and books, including the 2019 Secured Transactions Law Reform in Africa, as well as policy reports, including the 2025 Knowledge Guide on Crop Receipts Finance. Marek is an elected member of the American Law Institute.

Dr. Marek Dubovec is the Director of Law Reform Programs at the International Law Institute (ILI). For over 15 years, Marek has been working with UNCITRAL and UNIDROIT to draft conventions, model laws, principles, and guides that assist States in modernizing their commercial law frameworks. He has worked on implementing these standards under projects funded by the World Bank Group, the EBRD, FSD-Kenya, and others. He has assisted countries in Africa (e.g., Kenya), Asia (e.g., the Philippines), Eastern Europe (e.g., Ukraine), the Middle East (e.g., the UAE), and Latin America (e.g., Colombia) with reforms of their frameworks on secured transactions, factoring, warehouse receipts, and related legislation. Marek has authored and co-authored numerous articles and books, including the 2019 Secured Transactions Law Reform in Africa, as well as policy reports, including the 2025 Knowledge Guide on Crop Receipts Finance. Marek is an elected member of the American Law Institute. Prof. Dr. Cecilia Fresnedo de Aguirre is former professor of Private International Law at the University of the Republic Law School, at the Catholic University of Uruguay Law School, at the Hague Academy of International Law and visiting professor at several universities in different countries. Director of the Post-graduate Centre of the Law School of the University of the Republic. Member and former Director of the Uruguayan Institute of Private International Law, member of the American Private International Law Association (ASADIP), member of the Consultative Board of Private Higher Education appointed by the Ministry of Education and Culture (2002), former and re-elected member of the Inter-American Juridical Committee of the OAS, member of the International Academy of Comparative Law, Associate Member of the Hispanic Portuguese American Filipino Institute of International Law (IHLADI), Associate Member of the Institut de Droit International, member of the Working Group in charge of elaborating a Draft Act on Private International Law (Act Nº 19.920, November 17, 2020), Attorney (1974), Doctor of Law and Social Sciences (1978), University of the Republic, School of Law. Lecturer and/or panellist in more than 120 seminars, conferences, congresses and workshops, including the Congress to celebrate the 75th Anniversary of the founding of UNIDROIT. Author of 26 books and more than 150 articles and chapters in Law Reviews -including the Unif. L. Rev- Rev. dr. unif. – and collective publications in Uruguay and abroad. Global professional experience as consultant and arbitrator.

Prof. Dr. Cecilia Fresnedo de Aguirre is former professor of Private International Law at the University of the Republic Law School, at the Catholic University of Uruguay Law School, at the Hague Academy of International Law and visiting professor at several universities in different countries. Director of the Post-graduate Centre of the Law School of the University of the Republic. Member and former Director of the Uruguayan Institute of Private International Law, member of the American Private International Law Association (ASADIP), member of the Consultative Board of Private Higher Education appointed by the Ministry of Education and Culture (2002), former and re-elected member of the Inter-American Juridical Committee of the OAS, member of the International Academy of Comparative Law, Associate Member of the Hispanic Portuguese American Filipino Institute of International Law (IHLADI), Associate Member of the Institut de Droit International, member of the Working Group in charge of elaborating a Draft Act on Private International Law (Act Nº 19.920, November 17, 2020), Attorney (1974), Doctor of Law and Social Sciences (1978), University of the Republic, School of Law. Lecturer and/or panellist in more than 120 seminars, conferences, congresses and workshops, including the Congress to celebrate the 75th Anniversary of the founding of UNIDROIT. Author of 26 books and more than 150 articles and chapters in Law Reviews -including the Unif. L. Rev- Rev. dr. unif. – and collective publications in Uruguay and abroad. Global professional experience as consultant and arbitrator. Etsuko Sugiyama is a Professor of Law at Faculty of Law, Graduate School of Law and School of Law at Hitotsubashi University in Japan.

Etsuko Sugiyama is a Professor of Law at Faculty of Law, Graduate School of Law and School of Law at Hitotsubashi University in Japan. John Sorabji is an Associate Professor of Law at University College London. His expertise is in civil procedural law and alternative dispute resolution, and he is particularly interested in access to and the delivery of effective civil justice. He is co-founder and co-director of UCL Laws’ Centre for Dispute Resolution. Outside academia, he was previously Deputy Private Secretary to HM King Charles III and before that Principal Legal Adviser to the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales and the Master of the Rolls, where he advised on constitutional issues and judicial governance.

John Sorabji is an Associate Professor of Law at University College London. His expertise is in civil procedural law and alternative dispute resolution, and he is particularly interested in access to and the delivery of effective civil justice. He is co-founder and co-director of UCL Laws’ Centre for Dispute Resolution. Outside academia, he was previously Deputy Private Secretary to HM King Charles III and before that Principal Legal Adviser to the Lord Chief Justice of England and Wales and the Master of the Rolls, where he advised on constitutional issues and judicial governance. Alexis Mourre, founding partner of Mourre Chessa Le Lay Arbitration – MCL Arbitration, has served as counsel, President of the Tribunal, Co-Arbitrator, Sole Arbitrator or Expert in more than 350 international arbitrations, both ad hoc and before most international arbitral

Alexis Mourre, founding partner of Mourre Chessa Le Lay Arbitration – MCL Arbitration, has served as counsel, President of the Tribunal, Co-Arbitrator, Sole Arbitrator or Expert in more than 350 international arbitrations, both ad hoc and before most international arbitral Diane P. Wood is the Director of The American Law Institute and a Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Chicago Law School, where she teaches in the areas of federal civil procedure, antitrust law, and international trade and business. Previously she served on the U.S. Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit, serving as Chief Judge from 2013 to 2020.

Diane P. Wood is the Director of The American Law Institute and a Senior Lecturer in Law at the University of Chicago Law School, where she teaches in the areas of federal civil procedure, antitrust law, and international trade and business. Previously she served on the U.S. Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit, serving as Chief Judge from 2013 to 2020. Dora Neo is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore and the founding Director of the Faculty’s Centre for Banking & Finance Law which she led for some ten years from 2013. She served as an expert in the Working Group on the UNCITRAL-UNIDROIT Model Law on Warehouse Receipts and its Guide to Enactment, is an Advisory Committee Member of the UNIDROIT Asian Transnational Law Centre and a UNIDROIT correspondent for Singapore. Her research interests include global developments in secured transactions law; modernisation of trade finance law; consumer protection in the finance industry and contract law. Her publications include Studies in the Contract Laws of Asia V: Ending and Changing Contracts (co-edited with M Chen-Wishart and S Vogenauer, Oxford University Press, forthcoming 2016); Secured Transactions Law in Asia: Principles, Perspectives and Reform (co-edited with L Gullifer, Hart Publishing, 2021); and Trade Finance: Technology, Innovation and Documentary Credits (co-edited with C Hare, Oxford University Press, 2021). From September to December 2025, she was an Academic Visitor at the Faculty of Law of the University of Cambridge, and concurrently, a Visiting Fellow at Wolfson College, Cambridge. She is a graduate of Oxford University and Harvard Law School and is a non-practicing member of the Bar in England and Wales (Gray’s Inn) and Singapore.

Dora Neo is an Associate Professor at the Faculty of Law, National University of Singapore and the founding Director of the Faculty’s Centre for Banking & Finance Law which she led for some ten years from 2013. She served as an expert in the Working Group on the UNCITRAL-UNIDROIT Model Law on Warehouse Receipts and its Guide to Enactment, is an Advisory Committee Member of the UNIDROIT Asian Transnational Law Centre and a UNIDROIT correspondent for Singapore. Her research interests include global developments in secured transactions law; modernisation of trade finance law; consumer protection in the finance industry and contract law. Her publications include Studies in the Contract Laws of Asia V: Ending and Changing Contracts (co-edited with M Chen-Wishart and S Vogenauer, Oxford University Press, forthcoming 2016); Secured Transactions Law in Asia: Principles, Perspectives and Reform (co-edited with L Gullifer, Hart Publishing, 2021); and Trade Finance: Technology, Innovation and Documentary Credits (co-edited with C Hare, Oxford University Press, 2021). From September to December 2025, she was an Academic Visitor at the Faculty of Law of the University of Cambridge, and concurrently, a Visiting Fellow at Wolfson College, Cambridge. She is a graduate of Oxford University and Harvard Law School and is a non-practicing member of the Bar in England and Wales (Gray’s Inn) and Singapore. Teresa Rodríguez de las Heras Ballell is the full Professor of Commercial Law at University Carlos III of Madrid, Spain.

Teresa Rodríguez de las Heras Ballell is the full Professor of Commercial Law at University Carlos III of Madrid, Spain. Dr Iyare Otabor-Olubor is a Senior Lecturer in Commercial Law at Aston University, Birmingham, UK. He is an expert in transnational commercial law, with a particular focus on the reform and modernisation of secured transactions law. His research engages deeply with questions of access to finance in emerging economies, fintech regulation, and he is interested in critical legal research methodologies, including doctrinal and empirical legal approaches. Iyare teaches commercial law and contributes to curriculum development within the law school. He is a Senior Fellow of Advance HE, reflecting his sustained commitment to excellence in teaching and learning. Iyare holds an LLB degree, an LLM in Commercial Law, and a PhD, and he has been called to the Nigerian Bar. He actively supervises doctoral researchers and serves on, and chairs, several committees within his university. He also collaborates with scholars and intergovernmental organisations on projects related to legal development and access to finance.

Dr Iyare Otabor-Olubor is a Senior Lecturer in Commercial Law at Aston University, Birmingham, UK. He is an expert in transnational commercial law, with a particular focus on the reform and modernisation of secured transactions law. His research engages deeply with questions of access to finance in emerging economies, fintech regulation, and he is interested in critical legal research methodologies, including doctrinal and empirical legal approaches. Iyare teaches commercial law and contributes to curriculum development within the law school. He is a Senior Fellow of Advance HE, reflecting his sustained commitment to excellence in teaching and learning. Iyare holds an LLB degree, an LLM in Commercial Law, and a PhD, and he has been called to the Nigerian Bar. He actively supervises doctoral researchers and serves on, and chairs, several committees within his university. He also collaborates with scholars and intergovernmental organisations on projects related to legal development and access to finance. Professor Garro is Honorary Professor of Law at the University of Buenos Aires and teaches at Columbia University School of Law, where he is Senior Research Scholar at the Parker School of Foreign and Comparative Law.

Professor Garro is Honorary Professor of Law at the University of Buenos Aires and teaches at Columbia University School of Law, where he is Senior Research Scholar at the Parker School of Foreign and Comparative Law. Professor Louise Gullifer KC (hon) FBA is Rouse Ball Professor of English Law at the University of Cambridge, and a fellow of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. She is currently Chair of the Cambridge Law Faculty. She was formerly Professor of Commercial Law at the University of Oxford and held a Fellowship at Harris Manchester College in 2000. She practised at the Bar for a number of years before becoming an academic, and is a Bencher of Gray’s Inn.

Professor Louise Gullifer KC (hon) FBA is Rouse Ball Professor of English Law at the University of Cambridge, and a fellow of Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. She is currently Chair of the Cambridge Law Faculty. She was formerly Professor of Commercial Law at the University of Oxford and held a Fellowship at Harris Manchester College in 2000. She practised at the Bar for a number of years before becoming an academic, and is a Bencher of Gray’s Inn. Rafael Castillo-Triana is a lawyer and consultant for the leasing industry with more than 40 years of experience in leasing. Experience in litigation, insurance, stock exchange, international banking and management of investment portfolios before 1982, from that year he dedicated his professional efforts to the leasing industry, first as turn-around manager of Leasing Grancolombiana S.A. (today Leasing Bancolombia), and founder and manager of the companies Megaleasing S.A. and Equileasing S.A. between 1987 and 1990. In 1988 he represented the Republic of Colombia in the negotiation, drafting and adoption of the UNIDROIT Convention on International Leasing of Ottawa, Canada, the basis of the laws of countries such as Panama and El Salvador (whose draft law he prepared). In 1990 he opened his legal practice specializing in leasing and in 1997 he was appointed director for Latin America of the global leasing consultancy, The Alta Group.

Rafael Castillo-Triana is a lawyer and consultant for the leasing industry with more than 40 years of experience in leasing. Experience in litigation, insurance, stock exchange, international banking and management of investment portfolios before 1982, from that year he dedicated his professional efforts to the leasing industry, first as turn-around manager of Leasing Grancolombiana S.A. (today Leasing Bancolombia), and founder and manager of the companies Megaleasing S.A. and Equileasing S.A. between 1987 and 1990. In 1988 he represented the Republic of Colombia in the negotiation, drafting and adoption of the UNIDROIT Convention on International Leasing of Ottawa, Canada, the basis of the laws of countries such as Panama and El Salvador (whose draft law he prepared). In 1990 he opened his legal practice specializing in leasing and in 1997 he was appointed director for Latin America of the global leasing consultancy, The Alta Group. Lauro Gama Jr. graduated from the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) in 1987 and was admitted in 1988 to the Brazilian Bar. He holds a Masters in International Relations (PUC-Rio, 1992), a LL.M degree in Comparative Law (McGill, 1999), and a Doctorate degree in International Law (Univ. São Paulo, 2004). He is currently Adjunct Professor at the Pontifical Catholic Univ. of Rio (PUC-Rio), where he teaches Private International Law, Contracts and International Commercial Arbitration. He has authored books and articles published in specialized journals. He participated in the working group of the UNIDROIT Principles (2008-2010) and also in the working group of the 2015 Hague Principles. Prof. Gama is member of the CISG Advisory Council. In 2016, Lauro lectured at the Hague Academy of International Law (“The UNIDROIT Principles as the law applicable to commercial contracts”, published in vol. 406 of the Collected Courses). To this date Lauro has acted as counsel and arbitrator in more than 150 cases, under the rules of ICC, LCIA, UNCITRAL and Brazilian arbitral institutions. Mr. Gama served as President of the Brazilian Arbitration Committee (CBAr) from 2013 to 2015, and as a Member of the ICC Court of International Arbitration from 2015 to 2021. He served as member of the Council of the ICC Institute of World Business Law (2019-2015) and currently served as emeritus member. He currently participates of the working group formed by UNIDROIT and the ICC WBL Institute to develop a legal framework for international investment contracts.

Lauro Gama Jr. graduated from the State University of Rio de Janeiro (UERJ) in 1987 and was admitted in 1988 to the Brazilian Bar. He holds a Masters in International Relations (PUC-Rio, 1992), a LL.M degree in Comparative Law (McGill, 1999), and a Doctorate degree in International Law (Univ. São Paulo, 2004). He is currently Adjunct Professor at the Pontifical Catholic Univ. of Rio (PUC-Rio), where he teaches Private International Law, Contracts and International Commercial Arbitration. He has authored books and articles published in specialized journals. He participated in the working group of the UNIDROIT Principles (2008-2010) and also in the working group of the 2015 Hague Principles. Prof. Gama is member of the CISG Advisory Council. In 2016, Lauro lectured at the Hague Academy of International Law (“The UNIDROIT Principles as the law applicable to commercial contracts”, published in vol. 406 of the Collected Courses). To this date Lauro has acted as counsel and arbitrator in more than 150 cases, under the rules of ICC, LCIA, UNCITRAL and Brazilian arbitral institutions. Mr. Gama served as President of the Brazilian Arbitration Committee (CBAr) from 2013 to 2015, and as a Member of the ICC Court of International Arbitration from 2015 to 2021. He served as member of the Council of the ICC Institute of World Business Law (2019-2015) and currently served as emeritus member. He currently participates of the working group formed by UNIDROIT and the ICC WBL Institute to develop a legal framework for international investment contracts. Prof. Andrés Jana is a founding partner of Jana & Gil, Dispute Resolution. He serves as Vice President of the International Court of Arbitration at the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), Chair of Working Group II on Dispute Settlement at the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL), Member of the Governing Board and Chair of the Judiciary Committee of the International Council for Commercial Arbitration (ICCA), and founding member and part of the governing board of the Latin American Arbitration Association (ALARB).

Prof. Andrés Jana is a founding partner of Jana & Gil, Dispute Resolution. He serves as Vice President of the International Court of Arbitration at the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), Chair of Working Group II on Dispute Settlement at the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL), Member of the Governing Board and Chair of the Judiciary Committee of the International Council for Commercial Arbitration (ICCA), and founding member and part of the governing board of the Latin American Arbitration Association (ALARB). Hiroo Sono, LL.M., University of Michigan Law School, is Professor of Law at Hokkaido University Law School, Japan. His main fields of research interest are contract law, international commercial law, and harmonization of private law. He has published extensively in Japanese and English in these fields.

Hiroo Sono, LL.M., University of Michigan Law School, is Professor of Law at Hokkaido University Law School, Japan. His main fields of research interest are contract law, international commercial law, and harmonization of private law. He has published extensively in Japanese and English in these fields. Christian Twigg-Flesner LL.B. PCHE Ph.D. (Sheffield) is Professor of Contract and Consumer Law at the University of Warwick. He is also serving as Managing Editor of the Journal of Consumer Policy. Before he joined Warwick, he worked at the University of Hull, latterly as Professor of Commercial Law. He previously worked at the University of Sheffield (2002-4) and Nottingham Trent University (1999-2002). He is a Fellow of the European Law Institute and served as co-reporter/person-with-file for the ELI Guiding Principles and Model Rules on Digital Assistants for Consumer Contracts (2025). His research and teaching interests cover Contract, Consumer and Commercial Law. He has a keen interest in the impact of digitalisation on these fields. He has written many articles, book chapters and books, including Foundations of International Commercial Law (Routledge, 2021). He has been involved in many projects throughout his career, including work in the Research Group on Existing EC Private Law (Acquis Group) and the EC Consumer Compendium project (2005), and has co-authored several reports that formed the basis of UK consumer law reform. Currently, his work frequently focuses on the relationship between law and digital technologies, both in respect of Consumer Law and International Commercial Law.

Christian Twigg-Flesner LL.B. PCHE Ph.D. (Sheffield) is Professor of Contract and Consumer Law at the University of Warwick. He is also serving as Managing Editor of the Journal of Consumer Policy. Before he joined Warwick, he worked at the University of Hull, latterly as Professor of Commercial Law. He previously worked at the University of Sheffield (2002-4) and Nottingham Trent University (1999-2002). He is a Fellow of the European Law Institute and served as co-reporter/person-with-file for the ELI Guiding Principles and Model Rules on Digital Assistants for Consumer Contracts (2025). His research and teaching interests cover Contract, Consumer and Commercial Law. He has a keen interest in the impact of digitalisation on these fields. He has written many articles, book chapters and books, including Foundations of International Commercial Law (Routledge, 2021). He has been involved in many projects throughout his career, including work in the Research Group on Existing EC Private Law (Acquis Group) and the EC Consumer Compendium project (2005), and has co-authored several reports that formed the basis of UK consumer law reform. Currently, his work frequently focuses on the relationship between law and digital technologies, both in respect of Consumer Law and International Commercial Law. Yesim M. Atamer holds the Chair for Private Law, Commercial Law, European and Comparative Law at University of Zurich, Faculty of Law. Her main areas of research are law of obligations, especially comparative contract law, harmonization of European contract law, law of domestic and international sale of goods, and regulation and contract law. As a scholar of the European Union Jean Monnet program, Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Max Planck Society, Swiss Institute of Comparative Law and the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (Unidroit) she has conducted research in Lausanne, Basel, Rome, Munich, Hamburg and Cambridge (USA). In 2007, she received the Distinguished Young Scientist Award from the Turkish Academy of Sciences, and in 2019, she was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Hamburg. She is elected titular member of the International Academy of Comparative Law, the International Academy of Commercial and Consumer Law, the Science Academy, Turkey, and the Academia Europaea. Atamer became elected member of the CISG Advisory Council in 2013. She is a contributor to the major commentary on the Unidroit Principles of International Commercial Contracts edited by Vogenauer (2nd edition Oxford University Press, 2015), the CISG commentary edited by Kröll, Mistelis and Perales Viscasillas (2nd edition, Hart Publishing, 2018) and the CISG commentary edited by Schlechtriem/Schwenzer/Schroeter (8th edition Beck/Nomos/ Hart Publishing, 2024). She has been active in legal practice as arbitrator and legal expert in national and international disputes.

Yesim M. Atamer holds the Chair for Private Law, Commercial Law, European and Comparative Law at University of Zurich, Faculty of Law. Her main areas of research are law of obligations, especially comparative contract law, harmonization of European contract law, law of domestic and international sale of goods, and regulation and contract law. As a scholar of the European Union Jean Monnet program, Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, Max Planck Society, Swiss Institute of Comparative Law and the International Institute for the Unification of Private Law (Unidroit) she has conducted research in Lausanne, Basel, Rome, Munich, Hamburg and Cambridge (USA). In 2007, she received the Distinguished Young Scientist Award from the Turkish Academy of Sciences, and in 2019, she was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of Hamburg. She is elected titular member of the International Academy of Comparative Law, the International Academy of Commercial and Consumer Law, the Science Academy, Turkey, and the Academia Europaea. Atamer became elected member of the CISG Advisory Council in 2013. She is a contributor to the major commentary on the Unidroit Principles of International Commercial Contracts edited by Vogenauer (2nd edition Oxford University Press, 2015), the CISG commentary edited by Kröll, Mistelis and Perales Viscasillas (2nd edition, Hart Publishing, 2018) and the CISG commentary edited by Schlechtriem/Schwenzer/Schroeter (8th edition Beck/Nomos/ Hart Publishing, 2024). She has been active in legal practice as arbitrator and legal expert in national and international disputes. Giuditta Cordero-Moss, Dr. juris (Oslo), PhD (Moscow), Professor, Oslo University.

Giuditta Cordero-Moss, Dr. juris (Oslo), PhD (Moscow), Professor, Oslo University. Professor Pilar Perales Viscasillas is a Full Professor of Commercial Law at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, currently on leave. She also earned her PhD at the same institution, where she served as Director of the Doctoral School and of the School of Law. She holds a Law degree from the Autonomous University of Madrid. Since 2018, she has been an independent board member of Mapfre S.A., and she also holds positions at Mapfre Global Risks and Mapfre Asistencia, where she serves as Vice Chair of the Board of Directors. She is a member of the Audit Committee and the Risk and Sustainability Committee.

Professor Pilar Perales Viscasillas is a Full Professor of Commercial Law at Universidad Carlos III de Madrid, currently on leave. She also earned her PhD at the same institution, where she served as Director of the Doctoral School and of the School of Law. She holds a Law degree from the Autonomous University of Madrid. Since 2018, she has been an independent board member of Mapfre S.A., and she also holds positions at Mapfre Global Risks and Mapfre Asistencia, where she serves as Vice Chair of the Board of Directors. She is a member of the Audit Committee and the Risk and Sustainability Committee. Risham Garg is a Professor of Law (2020) at the National Law University Delhi, India. He also serves as the Executive Director of the Center for Transnational Commercial Law (CTCL) and also of the Centre for Incubation, Innovation and Entrepreneurship (CIIE). He is also a Director of NLU Delhi Foundation, the not-for-profit co. and incubation centre promoted by NLUD.

Risham Garg is a Professor of Law (2020) at the National Law University Delhi, India. He also serves as the Executive Director of the Center for Transnational Commercial Law (CTCL) and also of the Centre for Incubation, Innovation and Entrepreneurship (CIIE). He is also a Director of NLU Delhi Foundation, the not-for-profit co. and incubation centre promoted by NLUD. Matthias Lehmann is a professor of Private, Private International and Comparative Law at the University of Vienna. His main interest is the cross-border aspect of banking and financial law, both from a regulatory and from a private law viewpoint. He is regularly a guest professor in various universities, including Sorbonne University, where he teaches a class on the crypto economy. He has been visiting academic at the London School of Economics and Political Science, at Oxford University and at Stanford University, and is regularly invited as a guest professor at various European Universities, including Sorbonne University (France), where he teaches a class on the law and regulation of crypto markets. Matthias is a member of the Council European Law Institute, the American Law Institute, the Academia Europaea and of the Academic Council of the European Banking Institute. He was a member of the European Commission’s Expert Group on Conflict of Laws Regarding Securities and Claims, and has worked with the UK Financial Markets Law Committee. He has been an observer to the UNIDROIT working group, digital assets and private law. Currently, he is a member of the UNIDROIT Working Groups on bank insolvency and verified carbon credits.

Matthias Lehmann is a professor of Private, Private International and Comparative Law at the University of Vienna. His main interest is the cross-border aspect of banking and financial law, both from a regulatory and from a private law viewpoint. He is regularly a guest professor in various universities, including Sorbonne University, where he teaches a class on the crypto economy. He has been visiting academic at the London School of Economics and Political Science, at Oxford University and at Stanford University, and is regularly invited as a guest professor at various European Universities, including Sorbonne University (France), where he teaches a class on the law and regulation of crypto markets. Matthias is a member of the Council European Law Institute, the American Law Institute, the Academia Europaea and of the Academic Council of the European Banking Institute. He was a member of the European Commission’s Expert Group on Conflict of Laws Regarding Securities and Claims, and has worked with the UK Financial Markets Law Committee. He has been an observer to the UNIDROIT working group, digital assets and private law. Currently, he is a member of the UNIDROIT Working Groups on bank insolvency and verified carbon credits. Charles W. Mooney, Jr. Charles A. Heimbold, Jr. Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School; J.D. (cum laude) Harvard Law School; B.A. (High Honors) University of Oklahoma; Partner Shearman & Sterling (1981-86). He is a leading legal scholar in the fields of commercial law and bankruptcy law. His book (with the late Steven Harris), Security Interests in Personal Property, is a widely adopted text used in law schools around the United States. Mooney was honored for his contributions to the uniform law process by the Oklahoma City University School of Law. The American College of Commercial Finance Lawyers awarded Mooney the Distinguished Service Award, the Grant Gilmore Award in recognition of superior writing in the field of commercial finance law, and the Harry C. Sigman Special Award for leadership on the 2022 UCC Amendments. Mooney also served as a Co-Reporter for the Drafting Committee for the Revision of UCC Article 9 (Secured Transactions) (1990-2000), as Reporter for the Revision of the UCC (Emerging Technologies, including new Article 12) (2021-22), as the ABA Liaison-Advisor to the Permanent Editorial Board for the UCC, and as a member of Council and Chair of the Committee on UCC of the ABA Business Law Section. He is a Fellow and former Director of the American College of Bankruptcy and American College of Commercial Finance Attorneys, and a member and former director, vice-president, and member of the Executive Committee of the International Insolvency Institute (III). Mooney served as a member of UNIDROIT Working Group on Digital Assets, head of III delegation to UNCITRAL Working Group VI (secured transactions), and as a U.S. Delegate at the Diplomatic Conferences for the UNIDROIT Leasing Convention, Cape Town Convention (Aircraft and MAC Protocols), and Geneva Securities Convention.

Charles W. Mooney, Jr. Charles A. Heimbold, Jr. Professor of Law Emeritus, University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School; J.D. (cum laude) Harvard Law School; B.A. (High Honors) University of Oklahoma; Partner Shearman & Sterling (1981-86). He is a leading legal scholar in the fields of commercial law and bankruptcy law. His book (with the late Steven Harris), Security Interests in Personal Property, is a widely adopted text used in law schools around the United States. Mooney was honored for his contributions to the uniform law process by the Oklahoma City University School of Law. The American College of Commercial Finance Lawyers awarded Mooney the Distinguished Service Award, the Grant Gilmore Award in recognition of superior writing in the field of commercial finance law, and the Harry C. Sigman Special Award for leadership on the 2022 UCC Amendments. Mooney also served as a Co-Reporter for the Drafting Committee for the Revision of UCC Article 9 (Secured Transactions) (1990-2000), as Reporter for the Revision of the UCC (Emerging Technologies, including new Article 12) (2021-22), as the ABA Liaison-Advisor to the Permanent Editorial Board for the UCC, and as a member of Council and Chair of the Committee on UCC of the ABA Business Law Section. He is a Fellow and former Director of the American College of Bankruptcy and American College of Commercial Finance Attorneys, and a member and former director, vice-president, and member of the Executive Committee of the International Insolvency Institute (III). Mooney served as a member of UNIDROIT Working Group on Digital Assets, head of III delegation to UNCITRAL Working Group VI (secured transactions), and as a U.S. Delegate at the Diplomatic Conferences for the UNIDROIT Leasing Convention, Cape Town Convention (Aircraft and MAC Protocols), and Geneva Securities Convention. Professor Dr. Matthias Haentjens holds the chair for civil law at Leiden University, the Netherlands. He also practices law as advocaat at De Brauw Blackstone Westbroek. He has been a deputy judge in the commercial law division of the Court of Amsterdam from 2019-2025.

Professor Dr. Matthias Haentjens holds the chair for civil law at Leiden University, the Netherlands. He also practices law as advocaat at De Brauw Blackstone Westbroek. He has been a deputy judge in the commercial law division of the Court of Amsterdam from 2019-2025. Ms. Elsie Addo Awadzi is a Visiting Fellow at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford. She is a multi-disciplinary professional with 30 years of professional experience working in various capacities in Africa and internationally. Her experience spans economic governance, international financial institutions, financial services regulation, and crisis management. Until recently, she served as a Deputy Governor of the Bank of Ghana for seven years, where she led major reforms that helped to strengthen the banking system, including navigating it through a systemic banking crisis and a public debt restructuring exercise. Before then, she was Senior Counsel, Financial and Fiscal Law at the IMF, where she worked for six years helping several IMF member countries design and implement effective banking regulatory and crisis management frameworks, and fiscal governance frameworks. Before her IMF role, she held various portfolios in Ghana, including as a Commissioner of Ghana’s Securities & Exchange Commission for six years, where she played a key role in designing policies, rules, surveillance, and enforcement mechanisms for Ghana’s then-nascent capital market. She also consulted extensively for local and foreign businesses, private equity/venture capital funds, public sector clients, and development partners. Her earlier career saw her working in corporate law and a brief stint in bank treasury operations. She holds academic qualifications from Georgetown University Law Center (LL.M with Distinction in International Business & Economic Law 2012); University of Ghana Business School (M.B.A. Finance 2000), the Ghana School of Law (Qualifying Certificate in Law 1995), and the University of Ghana Law Faculty (LL.B 1993).

Ms. Elsie Addo Awadzi is a Visiting Fellow at the Blavatnik School of Government, University of Oxford. She is a multi-disciplinary professional with 30 years of professional experience working in various capacities in Africa and internationally. Her experience spans economic governance, international financial institutions, financial services regulation, and crisis management. Until recently, she served as a Deputy Governor of the Bank of Ghana for seven years, where she led major reforms that helped to strengthen the banking system, including navigating it through a systemic banking crisis and a public debt restructuring exercise. Before then, she was Senior Counsel, Financial and Fiscal Law at the IMF, where she worked for six years helping several IMF member countries design and implement effective banking regulatory and crisis management frameworks, and fiscal governance frameworks. Before her IMF role, she held various portfolios in Ghana, including as a Commissioner of Ghana’s Securities & Exchange Commission for six years, where she played a key role in designing policies, rules, surveillance, and enforcement mechanisms for Ghana’s then-nascent capital market. She also consulted extensively for local and foreign businesses, private equity/venture capital funds, public sector clients, and development partners. Her earlier career saw her working in corporate law and a brief stint in bank treasury operations. She holds academic qualifications from Georgetown University Law Center (LL.M with Distinction in International Business & Economic Law 2012); University of Ghana Business School (M.B.A. Finance 2000), the Ghana School of Law (Qualifying Certificate in Law 1995), and the University of Ghana Law Faculty (LL.B 1993). Dr Ole Böger is a Judge in Banking and Criminal matters at the Hanseatic Court of Appeal (Hanseatisches Oberlandesgericht) in Bremen, Germany, and a Lecturer at the University of Bremen. Since 2022, he is a Correspondent of UNIDROIT for Germany. Previously, he has been, amongst others, a Desk Officer at the German Federal Ministry of Justice and for Consumer Protection (2013-2016), a Legal Officer at UNIDROIT working on the Principles of Close-Out Netting (2012-2013) and a research assistant at the Max-Planck-Institute for Foreign and Comparative Private Law in Hamburg, Germany (2003-2008). He has represented the German government in UNCITRAL Working Groups and at UNIDROIT, specifically in the preparation and adoption of the MAC Protocol to the Cape Town Convention, and he is an Ex officio Observer to the Preparatory Commission for the Establishment of the International Registry for MAC equipment, as well as a member of the Commission of Experts to the Supervisory Authority of the Luxembourg Rail Protocol. Recently, he has been an external consultant to secured transactions law reform projects of the World Bank in Suriname (2016), Greece (2020) and Lebanon (2021). Dr Böger holds law degrees of the University of Göttingen in Germany and King’s College London (UK) and he has authored numerous publications with a focus on international secured transactions law and the law of payment services.

Dr Ole Böger is a Judge in Banking and Criminal matters at the Hanseatic Court of Appeal (Hanseatisches Oberlandesgericht) in Bremen, Germany, and a Lecturer at the University of Bremen. Since 2022, he is a Correspondent of UNIDROIT for Germany. Previously, he has been, amongst others, a Desk Officer at the German Federal Ministry of Justice and for Consumer Protection (2013-2016), a Legal Officer at UNIDROIT working on the Principles of Close-Out Netting (2012-2013) and a research assistant at the Max-Planck-Institute for Foreign and Comparative Private Law in Hamburg, Germany (2003-2008). He has represented the German government in UNCITRAL Working Groups and at UNIDROIT, specifically in the preparation and adoption of the MAC Protocol to the Cape Town Convention, and he is an Ex officio Observer to the Preparatory Commission for the Establishment of the International Registry for MAC equipment, as well as a member of the Commission of Experts to the Supervisory Authority of the Luxembourg Rail Protocol. Recently, he has been an external consultant to secured transactions law reform projects of the World Bank in Suriname (2016), Greece (2020) and Lebanon (2021). Dr Böger holds law degrees of the University of Göttingen in Germany and King’s College London (UK) and he has authored numerous publications with a focus on international secured transactions law and the law of payment services. Megumi Hara is Professor of Law at Chuo University, Tokyo, where she teaches property law, contract law, secured transactions, and trust law. Her research focuses on asset-based finance and the conceptual structure of property rights. Before joining Chuo, she taught at Kyushu University and Gakushuin University and has also given courses at the University of Tokyo and Keio University.

Megumi Hara is Professor of Law at Chuo University, Tokyo, where she teaches property law, contract law, secured transactions, and trust law. Her research focuses on asset-based finance and the conceptual structure of property rights. Before joining Chuo, she taught at Kyushu University and Gakushuin University and has also given courses at the University of Tokyo and Keio University. Dr Janis Sarra